The Critical Decentralisation Cluster at Chaos Communication Congress (36C3) is an area and grouping of similar minded projects, which are offering workshops and host a space to critically discuss the future of decentralisation.

The cluster at 36C3 is organised by RIAT and the Monero Community. We also host other assemblies in the categories Privacy & Anonymity, Coded Cultures and Open Hardware.

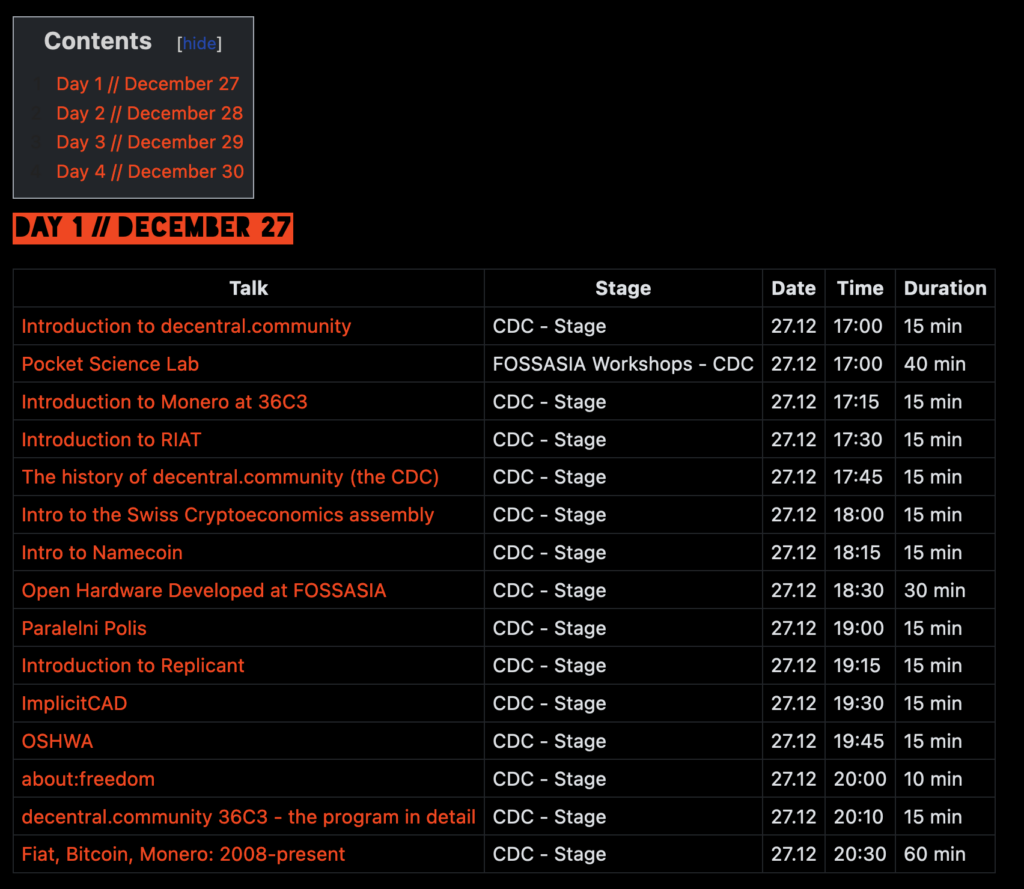

The cluster consists of a recording stage as well as workshop areas for the assemblies and similar minded groups and projects. Part of the cluster is a coffee area from Paralelni Polis, as well as lots of space to hack, work, and learn.

The Chaos Computer Club (CCC) is the largest (and oldest) hacker association in Europe and was founded in 1981. The annual Chaos Communication Congress takes place end of the year, since 1984. It is considered one of the largest (over 15,000 attendees) events of this kind, alongside the DEF CON in Las Vegas.

- Critical Decentralisation Cluster (36c3) Livestream – Friday

- Critical Decentralisation Cluster (36c3) Livestream – Saturday

- Critical Decentralisation Cluster (36c3) Livestream – Sunday

- Critical Decentralisation Cluster (36c3) Livestream – Monday

Critical Decentralisation points to disruptive events of history starting from the “Micro-Computing Revolution” in the 1970s, which spawned counter-cultures such as cryptoanarchists and cypherpunks. In the 1970s three different developments came about allowing individuals with modest computing resources to encrypt communication: the ciphers DES and RSA, as well as the Diffie-Hellman key exchange. Computers “[…] were gradually coming to be seen as tools of empowerment and autonomy rather than instruments of the state. These were the seeds of the ‘crypto dream.’” (Narayanan, 2013)

The ever-growing popularity of mobile devices, ubiquitous technology and (digital/global) real-time communication introduced challenges for technology appropriation and technology-based production cultures. The “smart devices” (tablets, smartphones, etc.) introduced an interface structure that is more intuitive, more easy to use, but also much more closed and opaque. Jonathan Zittrain criticized the dominance of smart devices, describing them as “tethered appliances” (Zittrain, 2006) – a way of tying end-users to the manufacturers. The principle of “closedness” that defines these tethered appliances refers to the hardware itself, which cannot be changed or used in another way than designed (and in some cases cannot even be repaired) as well as to new unprecedented levels of control. The consequent rise of the app-stores signals the “decline of the World Wide Web” (Anderson & Wolff, 2010) and the transformation of free culture into a commercialized ecosystem (cf. Schäfer & Tarasiewicz, 2013). In addition to the closure and commercialization of smart devices, data surveillance has become not only very easy to conduct but a pervasive strategy of social control. Although decentralisation presents itself with an impressive history of “revolutions” (the “maker revolution”, “blockchain revolution”), these developments get commodified at an accelerated pace. While Bitcoin is said to have been introduced as a critique on the banking system (“Chancellor on Brink of Second Bailout for Banks” Nakamoto, 2008) it currently appears “as cryptoanarchistic as a car” and “provides all the tools to f* you” (Smuggler at HCPP, 2018). Critical Making and Repair Culture challenge the Maker Culture as unreflective and hedonized practice (cf. Hertz, 2012; Ratto & Ree, 2012). Open Hardware scraches the surface of which degree of “Openism” (RIAT, 2017) is acceptable to critical end users and developers. Convenience always beats security. Decentralisation is a process, and has to be constantly challenged.